Why I left the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (also known as the “Jesuits” and the “Society,” and abbreviated as “SJ”) is the largest Catholic religious order. I first learned of this global congregation in Religion class in elementary school when we studied the lives of the saints. I later met Jesuits through the charismatic renewal and in my undergraduate studies at Creighton University, a Jesuit institution.

I never would have imagined in my early university days that I would enter the Jesuits at 28, nor that I would leave the Jesuits three years later.

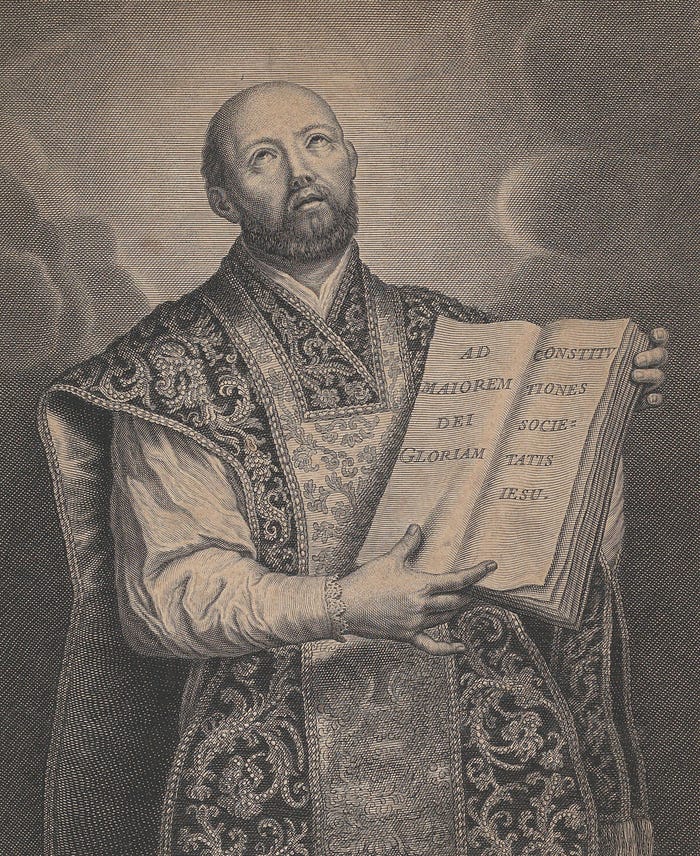

The Jesuits offer much to the Church and the world through their various works and their spirituality, rooted in the Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, the congregation’s founder. Ignatian spirituality is best understood a mysticism rooted in service and in finding God in everyday life. The Society’s worldwide reach and the spirituality of Ignatius attracted me to discern being a Jesuit. While I am no longer a Jesuit, I still hold in high esteem the congregation’s ministries and its spiritual foundation.

No religious order is perfect, and this includes the Jesuits. All religious orders comprise human actors who, though called by God, are imperfect. I had previously been in a religious order, so I knew this going into the Jesuits. But what I didn’t expect was the amount of egotism especially among several of those early in formation, and the amount of mean-spiritedness among several of those in the congregation.

Again, no one is perfect and no order is perfect. But even in the Intercessors of the Lamb, other than the foundress, I did not encounter much egotism, and the nastiness I mainly saw among those in leadership who were the result of carrying out the foundress’ bidding under pain of penalty.

During the Novitiate, the first two years of Jesuit formation in preparation for Vows, I contacted an older Jesuit about these instances in Jesuit community that surprised me. His response was that there was a lot of narcissism among Jesuits, and often narcissistic men are attracted to the Society.

I don’t know whether this is true or not, but it was validating to learn that my experience was not imaginary or in my head.

The other, more pressing negative experience I had in the Society, one that I did not realize until ten years later, was racism and cultural insensitivity.

As an international order, one would presume the Jesuits are experts in cultural sensitivity, both in terms of how members relate to people of various ethnicities, whether they be fellow Jesuits or the people they serve. I will say the Jesuits have an excellent ability to navigate different languages, customs and cultures, but this does not prevent one from holding inequitable beliefs nor acting on these beliefs.

My first memory recall of racism occurred during the summer of my first year in the Novitiate. I was in the dining area eating a sandwich during an early lunch when a group of my fellow Novices came into the kitchen, and out of nowhere one of them commented, “That must be how Indian people eat,” resulting in laughter from the others in his company.

One might logically ask, “What prompted this Novice to make that comment?” I really don’t know; it seemed like a non sequitor. I was not with the group that came into the kitchen, they were not speaking me nor I to them, and I was eating a very “American” meal, albeit well before noon.

However beyond those natural questions, I do not believe any of that information matters. This Novice called me out for being Indian in a matter that suggested I was less-than, and received complicit laughter from his fellows in response as opposed to being challenged for causing this derision. His public demonstration was shameful and humiliating not just towards me but a shameful and humiliating act in itself. Moreover, he involved my race in a negative way, and there is no excuse other than to call this behavior racist.

I was hurt and appalled by this statement, and communicated this to my Novice Master.

The Novice Master’s response was along the lines of, “Oh, I don’t think he meant anything bad by that, he’s a good guy and he really likes you.”

The Novice Master denied my experience of racism, the offending Novice had never been confronted for his racist statement, and I continued to live in a community of mainly White men feeling like an outsider, especially when racism goes unchallenged.

The Novice Master’s response is also reflective of the theme in Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility.

As I reflected more deeply about my Novitiate experience, racism and cultural insensitivity had a more prevalent undercurrent.

My Novice mates repeatedly critiqued me for appearing to them not “vulnerable enough,” my faith sharings sounding to them prepared and a bit too “put together.” The Novice Master joined in with these critiques.

If my Novice mates focused on the content of what I shared rather than how I appeared to them, there was nothing about my private life that I was not hiding. I was very honest and transparent.

But if the issue they found was that I sounded too “put together” in my sharings, are they implying that one can only share vulnerably by using phrases such as “uh,” “and like,” “where was I going with that,” “I lost my train of thought,” etc.?

Not to diminish anyone using such phrases, but believing that one could only share vulnerably by speaking in that manner, and conversely one who doesn’t speak in that manner must not be vulnerable, is a completely false dichotomy and states more about the interpreter than the person being interpreted.

Moreover, this might be an “American” interpretation on how one might speak vulnerably, which might not true in itself nor is it true when applied to persons of various cultures.

I experienced much confusion and perplexity receiving these critiques. There might have been even greater context for a cultural misunderstanding. I grew up in a very private culture. Our family did not talk about matters in the home outside of the home such as if one of my parents lost his/her job, if someone in our family has a grave health issue, if one of us kids did not do well in school, etc. My family tightly held any information that could lead to public gossip and shame.

Further, being an immigrant Indian family often living in neighborhoods that had few Indian families caused us to feel and be inward since this is where we felt safe. We did not necessarily feel safe and comfortable to be as we were among our neighbors for fear of being judged as different or strange. In my family there was a great deal of protectiveness that we incorporated into our public lives.

My faith sharings were transparent and personal, but my day-to-day activities could be viewed by someone as guarded and private, thereby warranting someone who doesn’t know the context to make such an assessment. There was no ill will on my part; I only knew what I knew and while I sought to be an open person, I had a tougher mountain to climb to overcome an inherently guarded upbringing.

The problem hitherto was that neither my Novice mates nor the Novice Master ever expressed any curiosity or openness to the possibility of a cultural misunderstanding and instead passed harsh judgment towards me. Novitiate Informationes (a form of evaluation used in the Jesuits; in the Novitiate this was done by peers) gave Novices ammunition to hurl towards those they might have disagreed with or did not fully like, and following the second juncture of this exercise, I believe the Novice Master took these reviews and criticisms at face value.

But if these criticisms were a consistent and important issue, there ought to have been a more loving and charitable conversation around this matter coupled with an invitation of curiosity as opposed to accusation.

However, I received none of that.

These experiences resulted in tremendous anxiety and stress during my Novitiate experience. During the Vow Triduum (short retreat prior to the profession of Vows), I experienced much sadness as a result of this experience, and had I known what I know now, I ought to have left the Jesuits for such terrible treatment, particularly for causing me to feel like an outsider more than I already felt when I entered the Society.

Instead of feeling welcome in the Novitiate community to be who I am, I felt pressured to be someone else and to fit in. While Ignatian Spirituality promotes God working in a person according to one’s uniqueness, the Novitiate, when not properly guided, can turn into uniformity and groupthink coupled with favoritism and popularity contests.

The majority of my Novice mates were more extroverted than me. As such, my Novice class generally enjoyed continued togetherness outside of scheduled Novitiate activities, mainly comprising standing around the rec room in the late hours chatting or watching Glee, Billy Elliot or another show that was not of interest to me.

After hours of being together, I was exhausted. At night I might occasionally hang around with the other guys but I often needed to go to my room either to recharge or to go to bed early. I enjoyed reading, and often only had the chance to do so freely at night. Additionally I preferred to wake up early, pray and/or go on a long jog. In the afternoons I might search the Novitiate library for treasures, read or use the Novitiate gym.

However, part of the direct criticism against me as well as indirect references caused me to feel like I was wrong for being different and having different interests and outlets. I instead felt pressure both from the Novice Master and the other Novices to be “like one of the other guys” and to regularly participate in such activities in my free time. I was encouraged and exhorted to follow the dominant herd rather than have my differences respected and reverenced. And for someone like myself with a different culture and skin color, if my differing preferences were not respected, it would suggest different ethnicity was also not respected.

Part of fitting in included imitating an Indian accent to gain approval. There had been a constant joke among my Novice mates on Paul Coutinho, a former Jesuit priest of Indian origin, and we would imitate his accent. At my first Novitiate Formation Play, I utilized the Indian accent for laughs. And at a Novitiate Summer Talent Show, there was a skit where someone was making fun of me for smelling like I was living in Calcutta. An Indian Jesuit priest was present for this skit and I remember him seeming disturbed by this presentation, and rightfully so.

I was blind in how I was complicit in this form of self-racism (and self-hatred) as a means of fitting in and seeming like I was “one of them.” However I was wrong, and members of the Society were wrong for laughing along at a caricature that promoted racial inequity.

The only time anyone had ever asked or acknowledged how I was doing in the Novitiate being of Indian origin was during my three-month assignment in Honduras when I met with the Central American Provincial. His question was insightful, having previously been the Novice Master for his Province. I recall stating something generic but looking back, there was so much I could have and should have said, but I had spent so much time denying who I am to fit in seamlessly in the Society of Jesus. But it took a Central American Jesuit to ask and become sensitive to this important matter.

After Vows, I found a good and perceptive superior in my Rector during graduate studies. I really found him sensitive to me and to my uniqueness, and I am forever grateful for his role in my formation. Potentially it was his own formation and/or his ministry in another continent for several years that enabled this sensitivity, but I just felt that my Rector “got” me. I knew that he trusted me and loved me just as I am. Unlike the Novitiate, my Rector allowed to me who I am and not someone else. Regardless if I seemed to him to be an introvert or extrovert, my Rector supported whatever activities and outlets that would offer me the most life and positivity. The Rector never insisted that I stay late at a house social gathering or make a point to join in with the other community members watching Glee.

During my first weekend in the house of studies, my Rector contacted the US Syro-Malabar Eparchy to obtain collaboration for my liturgical formation, as well as any other guidance that could benefit my formation. He encouraged me to frequent a nearby Syro-Malabar parish as well as to do whatever I needed to do obtain a deeper sense of cultural identity, knowing that neither he nor the community at the house of studies could offer that. I believe these experiences offered me positive identity and growth as well as encouraged me to take the bold step to propose going to Kerala, India during the summer following my first year in the house of studies.

The other fellow members in formation at this house did not express direct racism or cultural insensitivity, at least none insomuch that I can readily recall, however I do remember certain people who were quite mean to me and I interpreted this meanness to me being different. Looking back, it could have been that or it could have been something else, however there is no place for that type of treatment. Rather, this unkindness reinforced the belief that I was different and that I didn’t belong.

One of my last major events in the Society was the 2012 priestly ordination. While normally this is a wonderful and joyful gathering, I hated every minute of it. Being in the vicinity of my Novice mates and Novice Master reminded me of the years of culmination of feeling like an outsider in the Jesuits, resulting in the weekend feeling rather oppressive for me. I was looking forward to my trip to Kerala, idyllically anticipating that I might finally find a place of acceptance in the Society of Jesus.

There were many moments during that ordination weekend that ought to have brought about consolation. Other than the obvious — two members of the Society being ordained to the priesthood — I had been entrusted the special and difficult task of holding the Lectionary as an altar server for the archbishop, who preferred to have his hands outstretched in prayer while the altar server turned the pages for him (while reading the pages backwards). I was able to perform this task to the approval of the archbishop, and received generous recognition from my Formation Assistant and the Master of Ceremonies for my participation.

But outside of this, I felt alone and an outsider to the broader Jesuit community at the gathering. My only value seemed to be functional, not intrinsic. In my heart, I believe I knew this would be the last ordination I would attend as a Jesuit.

Following the ordinations, I went to Kerala. I had many wonderful experiences with the Jesuits I lived with there as well as in learning the Syro-Malabar Rite and the Malayalam language. However, at the adjacent Jesuit community attached to the Society’s primary and secondary school, the Jesuit principal had constantly taunted me for my beginner level comprehension of the Malayalam language, my American accent and his inability to understand my English because of it, and how my parents had “failed me” for not properly teaching me Malayalam.

The Jesuits in Kerala could not appreciate what Malayalees living outside of Kerala had to endure to assimilate into a new country. I was born in Louisiana, which did not have an immigrant Malayalee community. My parents believed it would be most proper that their children would learn English well and fit in with American society. The process of assimilation can impede maintaining cultural identity, including but not limited to language. This was not a fault of my parents; this was a means for survival.

In America I am an outsider, even among the Jesuits. In India I am an outsider, even among the Jesuits.

When I left Kerala, I was ready to be done with the Jesuits. I wrestled with these feelings because I had such wonderful experiences in prayer and active ministry. And I could not put my finger on the pulse of why I wanted to leave.

But after much reflection, I am now aware that the racism and mistreatment I experienced in the Society of Jesus is the primary reason why I left.

I would agree that if God had given me the grace to overcome such difficult experiences, then God might truly have been calling me to remain in the Society.

However, regardless of the presence or “absence” of grace, such difficult experiences are inexcusable and un-Christian.

I left the Society because it was not a welcoming home for me. It did not reflect or reinforce the love that the Trinity has for me and incessantly expresses toward me. My experience of the Society and of God were incompatible, and I found greater freedom and purpose to enter into Trinitarian communion after leaving the Jesuits.

While these experiences of racism and cultural insensitivity are abhorrent, I am encouraged that the Jesuits have undergone much growth in these areas since I departed in 2012. Namely, the acknowledgement of the Society’s involvement in slavery has brought awareness to the congregation to reflect on racism. Additionally, the events of the killing of George Floyd and several others encouraged many in the Church, including the Jesuits, to undergo a deeper examination on racism.

In fact, I learned that conversations on racism are now occurring in the Novitiate and in houses of formation, and the Jesuits who are early in their formation are encouraging much internal and external work on racism. These instances are a sign of hope that if someone like me were to enter the Jesuits in the US today, his experience of racism and cultural insensitivity might not be as severe as I had recounted.

Lastly, I recently shared my experience of racism and cultural insensitivity with the current Provincial of my former province, and I believe he and the province are taking my experiences into consideration seriously, both in terms of contrition and in how to be better members of the Body of Christ.

The gift of the Spiritual Exercises allowed me to reflect on past hurts experienced in the Jesuits, voice these hurts and seeking healing from God and through closure. While the Jesuits, like any religious order, are imperfect, God has given them the gift of leading people closer to Jesus and desiring to dedicate themselves to discerning and committing to the Will of God. I am grateful for the Society of Jesus and I pray that they may be strengthened in their mission in the Church and the world.